USE MENU ABOVE TO VIEW MORE IN THIS SERIES

If only she'd asked for her kiss. The thought haunts Patty Hindes.

It haunts her the way so many thoughts of that day haunt her, the way widows so often are haunted by questions that have no answers, by wishes that can't be fulfilled, by happenstance that only destiny had the power to change.

The lost kiss was happenstance much like the lost clutch pin.

Had she gotten her kiss, it would have delayed Corey's departure. Perhaps only by seconds. Maybe as long as a minute or two. Either way, enough.

Either way, enough time that he and his motorcycle wouldn't have been on the deadly spot on Rand Road at the moment the Mercedes turned left across his path.

And if it hadn't been for a broken clutch pin, Patty would have ridden with him and somehow, she thinks, she would have been able to warn him about the other driver.

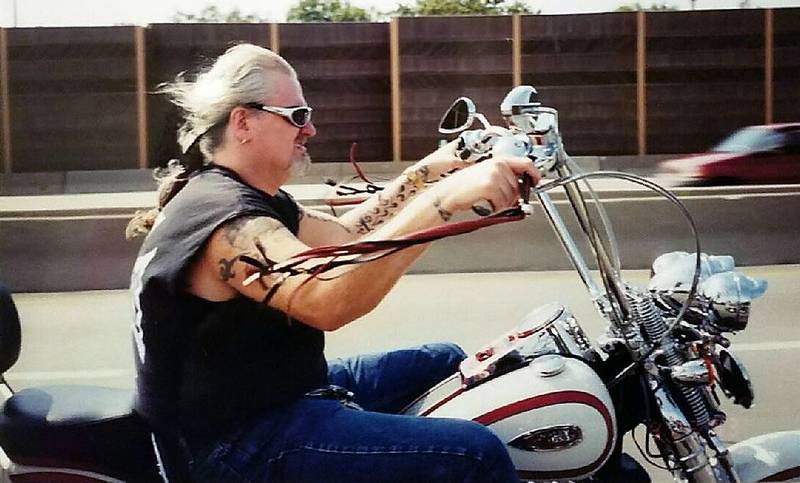

Courtesy of the Hindes family.

Patty Hindes and her late husband Corey.

I say, "If you had been with him, most likely the only thing that would have been different is that you would have been killed too, not just Corey."

She is neither sold nor comforted.

"If I would have been with him, I could have done something."

At times, her grief comes pouring out of the darkness like night sweats with such a terrible sense of helplessness.

But helplessness is not her nature. She's a computer programmer, so her nature is to solve problems, to make things work. Helplessness goes against her grain.

In characterizing her grief, she's more inclined toward C.S. Lewis. Not so much helplessness as fear.

In our many interviews since Corey's death in September 2016, I often ask out of the blue for her to describe how whatever day it is feels to her, and most frequently, she resorts to the legendary Christian writer:

"No one ever told me that grief felt so like fear."

She savors the quotation as if it is Scripture.

Patty doesn't recite the extended passage from A Grief Observed, Lewis' 1961 reflections on the death of his wife. But later, when I search out the text, it vibrates with echoes from my months of conversation with her.

Donald Westlake's essay becomes a short film, thanks to his daughter. A Straight From the Source story.

Writing a year after his 45-year-old wife's death and a year before his own, Lewis describes his bereavement like this:

"No one ever told me that grief felt so like fear. I am not afraid but the sensation is like being afraid. The same fluttering in the stomach, the same restlessness, the yawning. I keep on swallowing.

"At other times, it feels like being mildly drunk or concussed. There is a sort of invisible blanket between the world and me. I find it hard to take in what anyone says. Or perhaps, hard to want to take it in. It is so uninteresting. Yet I want the others to be about me. I dread the moments when the house is empty. If only they would talk to one another and not to me."

These are neither Patty's words nor her similes, but they capture so much of what she has tried to tell me about her loss.

"Fear," she says. "There's no word for fear that fits what it's like to lose the love of your life. 'Terror' doesn't fit. It's so overwhelming, this fear of life."

It is fear. And it is helplessness.

It is both.

A year ago, she took a trip to Tucson to get together for Easter with Corey's brother, Camdon Hindes, his dad, Mike Hindes, and about a dozen other relatives, "the Arizona family, as we call them."

Before the trip, she had gone through Corey's things and came across his high school class ring.

"I knew he would want his brother to have it," Patty said, "and it was too much to be around the house."

So she decided to head out of town.

A half year removed from Corey's death, she thought it would be good for the in-laws to see her when she wasn't "incoherent" anymore. The trip was a good getaway and a chance to make sure her son Connor stayed in touch with that side of the family.

But it was a keep-moving thing, not a re-emergence thing.

"It's all melancholy to me," she said. "It was nicer than sitting at home. And it was nice being surrounded by family."

It's been a year and a half since her dark September. Widowhood didn't stop at an anniversary. There was no celebration of reaching the end of it. It persists. It is the new normal.

Patty views the world as filled with two kinds of people: those widowed and those not.

I tell her that by writing about her experience, I hope we can help others prepare for what the loss is like, and she loses patience. I'm not listening to her, she says with more than a little exasperation.

Those not widowed may think they understand, she says, but they don't. And they can't.

And those widowed can never re-enter the fraternity of the non-widowed.

Their lives changed forever when they lost their spouses.

It may be possible to move forward, but it is not possible to go back.

"I can't explain it to you," Patty says, with frustration building. "It's impossible to explain. You can't understand unless you go through it."

She recalls Corey standing that afternoon by the chopper in their Arlington Heights garage. He stored two motorcycles there and favored the classic '97 Harley-Davidson Heritage Springer.

But that day, Corey drove the chopper, a custom kit bike with extreme angles and high handlebars, the seat positioned far to the back like a throne giving a tall, muscular, full-bearded man like Corey a swashbuckling appearance. To see his profile as he rode -- a big longhaired rebel, sleeveless and peppered with tattoos, big and brawny with powerful arms, thick chest and angular jaw -- was to imagine him sketched in pen-and-ink on that bike, so classic was the pose.

The chopper roared with style, to be sure, and drew comments.

Courtesy of the Hindes family.

Corey Hindes of Arlington Heights loved motorcycles, especially his Harley-Davidson Heritage Springer.

Even so, it was not Corey's favorite. His favorite was the Heritage Springer. Pure white with red pearl striping so sweet it would make the pavement swoon. The seat was long enough to allow Patty to slide in behind him for their rides. Talk about attracting comments. Corey couldn't go anywhere on the white Springer without hearing them. It was an attention magnet.

But that Sunday, it needed a repair. The clutch pin had broken. They didn't even know where it had fallen.

The clutch pin had broken on the Springer. So on the day Corey met his maker, he met him riding the chopper.

The seat on that motorcycle was small. It had room only for one.

For a moment, Patty is at the garage with him on that warm afternoon in 2016 at the back edge of summer. He is at the custom chopper, and she is wishing he would stay home. But she knows asking him to skip a motorcycle ride won't work.

"It's like asking me not to breathe," she had heard him say so many times before.

So she is wishing instead that she could ride with him. She loved snuggling in behind him on the back of the Springer, loved their rides together. She felt so safe with him, so connected to him, so alive with him.

She looks at him with kind of a sad face, nodding toward the white bike and lifting her eyebrows in the form of a question.

"You know you can't go," he says. "The shifter's broken."

She changes tactics. Does he really have to go?

"C'mon now, baby," he says. And then in a now-foreboding allusion to the approaching autumn, "This may be the last day I'll be able to ride."

She gives in and backs the car off the drive to give him room to get the chopper out. He pulls out on the bike and pauses to give her one of his beaming smiles.

Such a gift it is. He looks, in a word, joyful. She will remember it as perhaps the happiest he had ever seemed to her.

"I should stop him," she thinks. "I forgot to get my kiss."

But she's heading back to the house. He's on his bike, getting ready to leave.

And she lets it go. He drives off, never to share that kiss or any other, his date with cruel destiny seven minutes away in Palatine.

Back in the present, Patty says as flat as a monotone, as soft as a whisper: "I should have stopped him to get my kiss. That kills me. That may have bought him enough time."

On the night of his death, Patty, the family and a few close friends returned home from Lutheran General Hospital in Park Ridge. Many of the bikers who knew him turned up.

Connor, her son, then 18, led everyone in an impromptu Irish wake in the garage, toasting Corey's good name and memory with shots of Fireball Cinnamon Whisky.

"Holy cow," Patty said, "he's his father's son."

There were tributes; there were stories; there was laughter.

The memorial service took place a week later at Glueckert Funeral Home in Arlington Heights. The crowds poured in. The line for condolences streamed by Patty and the family for more than three hours, offering unabating hugs and words of solace.

At the end of the service, scores of bikers paid tribute with a ceremonial parade of motorcycles out to the house.

The widespread affection for Corey was evident, touching and comforting. It sustained the family through those early days.

And then, for the most part, everybody went on with their lives.

Patty's close friend Colette Celaya of Des Plaines stayed in touch, called often to check on her and continues to do so even now.

"She calls me every other day," Patty says, "and she doesn't hang up if I start to cry."

"You don't know what to do in a case like this," Celaya says. "You don't know what to say. Sometimes letting them talk is all they need."

But few other people checked on Patty with any regularity. The cookouts Corey used to host out by the backyard pool stopped. The friends who'd always been around no longer dropped over.

Corey had always been the life of the party, and without the life, there was no party.

People weren't unkind. They just had lives to live.

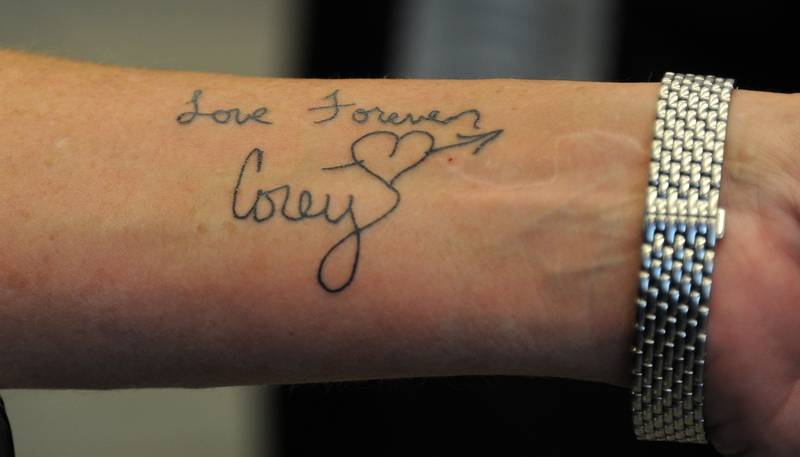

Mark Welsh | mwelsh@dailyherald.com

Patty Hindes of Arlington Heights modeled this tattoo from a note that had been written to her by her late husband Corey.

"They don't know how to reach out to me," Patty says. "They don't know what to say. It shocked me when no one came around. I wish they would have."

A month after Corey died, she got a back tattoo with his name above enormous angel's wings. Last summer, she added another, this one to her forearm, a facsimile of Corey's handwriting from a love note he'd written her.

They were tributes to Corey, but not, as yet, successful comforts.

"I can cover myself in tattoos," Patty says, "but it's not going to make me feel any better."

In a conversation a few months after Corey died, she recoiled at the idea of being described as a widow. She wasn't ready. She was his wife.

Telling the story of his crash, she interjected to volunteer that a doctor at the hospital told her a motorcycle helmet wouldn't have made any difference.

These were not small things. They matter to her.

About that same time, she joined a Facebook support group, Widow's Hope.

She couldn't bring herself to post anything at that stage. But she read. She could see some of herself in the posts that others left.

As time when on, she started adding her own posts -- at first anchored around her pain, but later, trying to comfort others.

"How do you get through this? How do you get through this? You help. You help others."

Toward the end of the 2000 movie Cast Away, Tom Hanks delivers a soliloquy that seems written to explain Patty's perseverance.

Hanks' character returns home after being marooned on a deserted island for four years only to find that his fiancé has moved on and married someone new. He sees parallels between his survival on the island and what he must do to survive the loss of his family.

"I gotta keep breathing," Hanks says in dialogue written by screenwriter William Broyles Jr. "Because tomorrow, the sun will rise. Who knows what the tide could bring?"

For 19 months, this is, in essence, what Patty has done. The tide will not bring Corey. But she's kept breathing. She's abided. She's kept moving. Not because she envisions happiness. But because she knows it's the only way forward.

She describes it as "pretending," that she's pretending things will be OK.

"Some days," she says, "are harder to pretend than others."

There have been days when she felt worthless, days when she caught herself enjoying a moment, nights when she couldn't sleep, days when she felt lost, days when she felt alone, days when she felt empty. So many of those days.

"You have to ride the tide of grief," she says. "It controls you. You do not control it."

Corey had been outgoing and confident. She had been introverted and uncertain. But with him, she had become a different person.

"As long as I was with him, I felt safe no matter what we did," she says. "I could have jumped out of an airplane with him. When I lost him, I lost that. That was a huge loss. It's very frightening."

Last August, she bought a motor scooter. She wasn't ready to ride Corey's Harley-Davidson yet, but she wanted to feel what it was like for him to ride, what it was like to be him. So she bought a motor scooter and rode it around the block a few times.

She decided she'd learn to ride it and then, perhaps by the end of his upcoming summer, be ready to ride his motorcycle.

She was nervous, but she said she realizes that she's got to do for herself now.

"I have to learn to do everything for myself," she says. "I can't depend on him anymore. Once you lose your spouse, the only person you can depend on is yourself."

The gravestone Patty designed was finished a year ago. It featured etchings with Corey's images including two dominant ones showing him on his motorcycle. "Wind in my hair, knees to the breeze," an inscription reads.

"I think he would be quite pleased if it's possible to be pleased with your own headstone," Patty said. "I didn't want people to go there and just see a plain stone."

When it was installed, she visited his grave in Elmhurst. It was the first time she did so alone. She brought a beer for him, his blanket, his favorite chocolate. Flowers for his grave and for his mother's.

She stayed for about two hours and felt better for having visited.

On the way back, she saw a truck barreling toward a motorcycle that had stopped on the road. She thought there was going to be a crash. She laid on the horn, and the truck driver hit his brakes, veered to the left, missing the Harley-Davidson.

"Maybe Corey just smiled at me and said, 'Good job, baby.'"

Signs from the afterworld. She doesn't know if she believes in them. She'd like to. She'd like to see them. Someone who had lost a daughter told her about seeing feathers everywhere.

Patty doesn't see feathers.

But a year ago, a half year after Corey's death, she was doing her Saturday duty at the Arlington Heights barber shop he left and that she now owns.

She was walking, head down the way her grief now has her walk, in front of the shop on the sidewalk where Corey used to park his motorcycle when he came into work. The walk was due to be torn up the following week for reconstruction.

There on the sidewalk, she saw a piece of metal.

Mystified at what it was, she held it up in front of a friend who was waiting in the shop.

"What is that?" she asked.

"Oh, my God," the friend said. "That's the clutch pin."